The Dark Ages was certainly a dark chapter of European history with many unfortunate and unpleasant incidences reported all across the continent. But stealing a wooden bucket and a dangerous war that followed which claimed thousands of lives, is a story that sounds too bizarre even for dark ages. However, sometimes the truth is indeed stranger than fiction and the war which occurred in 1325 AD in Northern Italy did have a few strange moments.

The background of War of the Bucket, which is also sometimes known as - War of the Oaken Bucket was laid many centuries before the war actually occurred in the 14th century. After the collapse of the Roman empire in the west, the whole social and political balance of Europe was greatly disturbed as chaos reigned supreme.

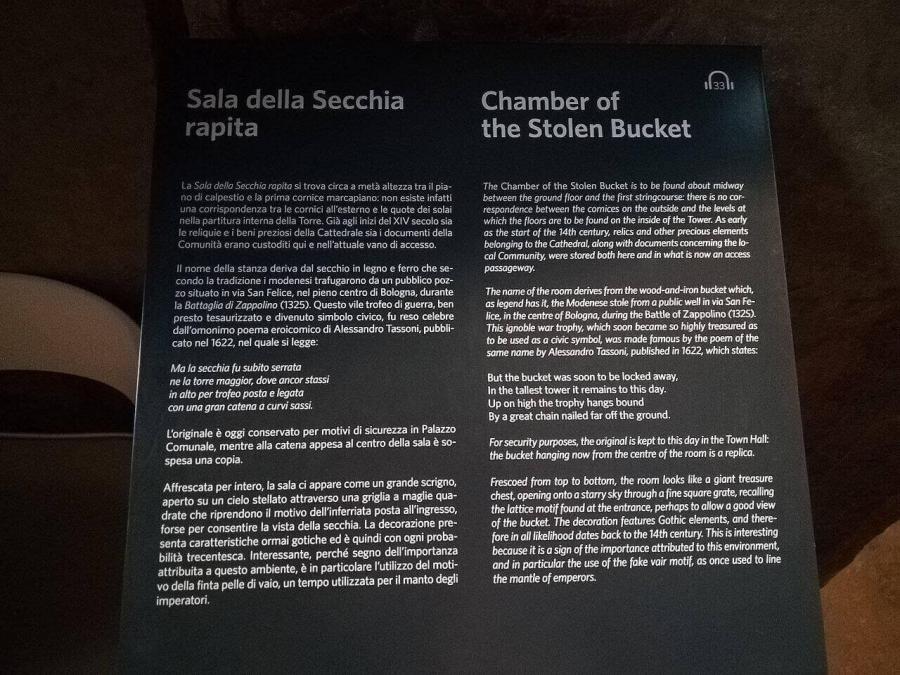

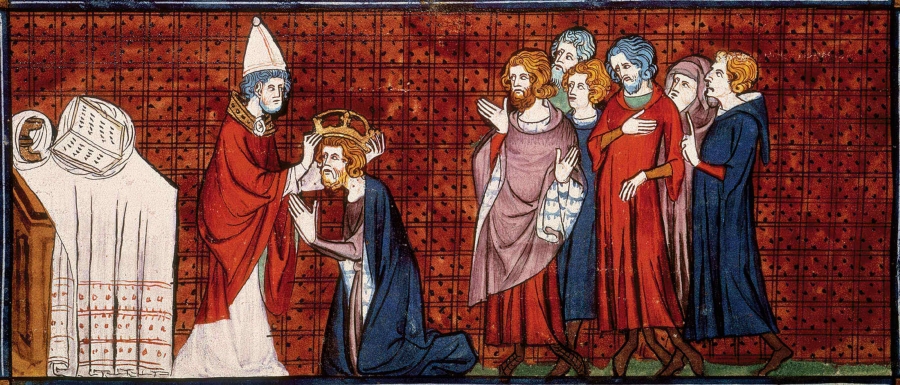

However, when Pope Leo III crowned the Frankish King Charlemagne as Emperor on 25 December 800, the title of emperor was once again created in western Europe, as the head of the Holy Roman Empire. Unfortunately, this empire, which continued for almost another thousand years, always suffered from a threat to its unity because of its decentralized structure, in form of the presence of multiple small kingdoms and other principalities under its domain.

The lords and princes of these small duchies and counties, although owned allegiance to the emperor, but had a great number of privileges and freedom when it came to governing their own territories. Making things more complicated was the involvement of clergy in the politics of the time. The Emperor and Papacy almost always competed for supremacy in the land, with the Emperor trying to put someone of his choice in Pope’s position and the Pope also trying a put a person favorable to his own interest in the Emperor’s throne, however that was not always feasible.

The emperor on his part knew that many territories in his domain were ruled by bishops and abbots. So, he tried to exercise more control over who finally would become bishops and abbots by putting his loyal followers and family friends in important positions. The Papacy, in turn, tried to reaffirm their own position, which led to the Investiture controversy, which ended in 1122 with a papal victory, however, the Emperor still retained considerable power.

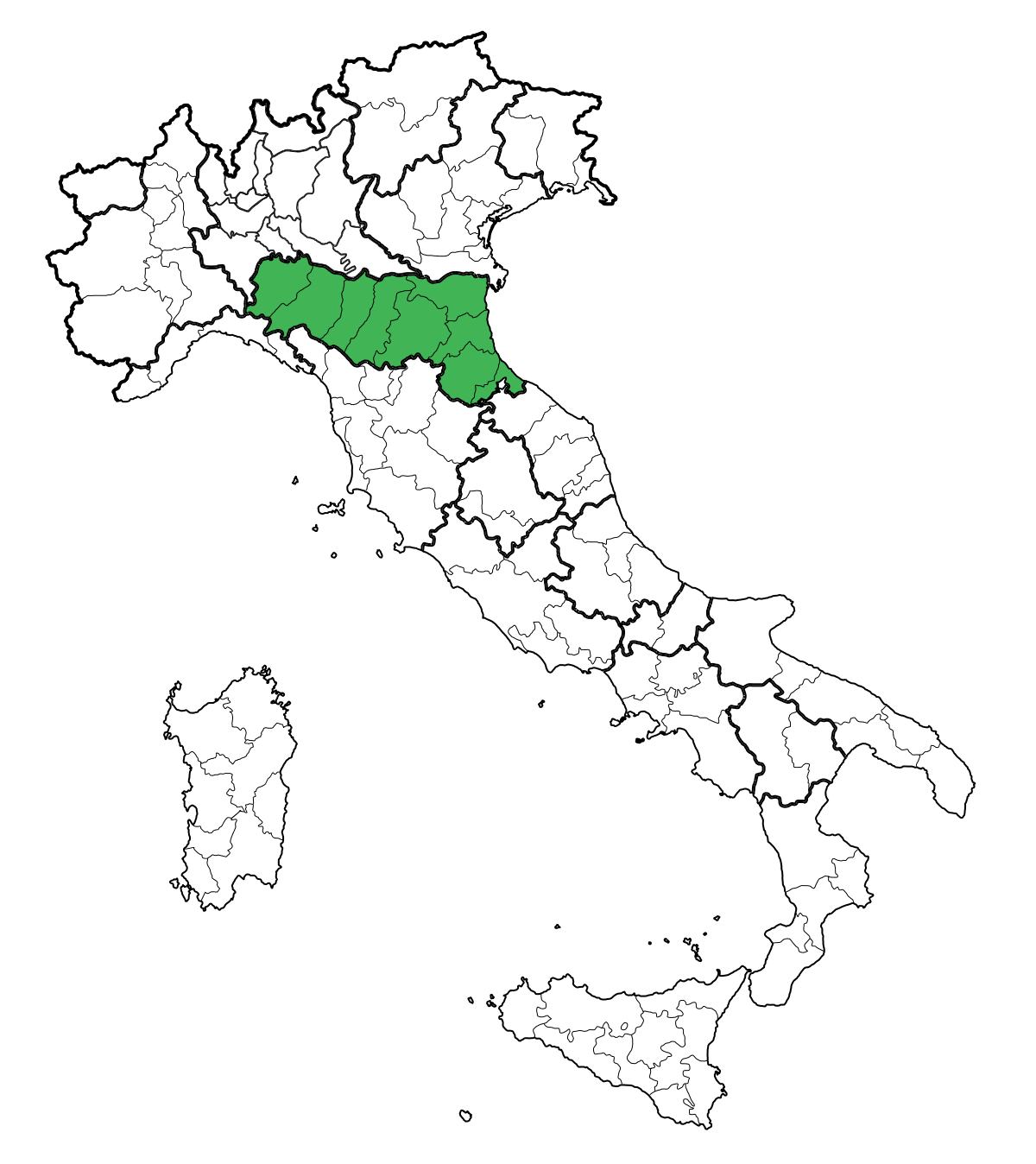

The animosity between the two sides continued to foster and divided the people and the principalities alike. These differences also affected the Italian city-states in central and northern Italy, who became divided into the Guelphs and Ghibellines factions. The Guelphs supported the Pope and the Ghibellines supported the Holy Roman Emperor. The conflicts between these Guelphs and Ghibellines formed an integral and important part of the internal politics of Italy. It is here that the story of the war of the oaken bucket starts.

As mentioned earlier the hostilities between the Guelphs and Ghibellines which lasted for many centuries had affected the city-states of Italy badly. It is in this disturbing time that two neighboring cities of northern Italy – Bologna and Modena, found themselves on different sides of the political divide. Bologna was Guelph whereas Modena was Ghibelline. Border disputes of the two neighbors (who were just around 31 miles apart) were exacerbated by their different political allegiance.

The Emperor supporting Modena & Pope supporting Bologna’s animosity had been present for a long time, much before the War of the Bucket actually happened in 1325. Both sides had been trying to seize lands of the other sides in battles between them, which occurred very frequently. However, most of the time, the gains achieved couldn’t be kept for a very long time in the volatile situation.

Although the fight between the two sides had been going on for a very long time, few specific battles deserve special mention. In the Battle of Fossalta, which occurred between the two sides in 1249, the Bolognese won the battle and Enzio of Sardinia (son of Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen) who was leading the Modenese was taken prisoner and spent the rest of his life as a prisoner in Bologna. In 1296, the Bolognese again attacked Modena, seizing towns of Savigno and Bazzano, which were soon recognized by the Pope as part of Bolognese territory.

In 1309, Passerino Bonacolsi, who was the loyal agent of the emperor Louise IV himself, became the ruler of Modena, Mantua, Parma, and Reggio; and he decided to take revenge on the Bolognese. Many attacks were launched against the Bolognese territories during his reign and Pope John XXIII soon declared Bonacolsi the enemy of the church. The Pope encouraged retribution against Bonacolsi, even assuring people that who would be able to teach Bonacolsi a lesson, would be forgiven for their actions, however grievous those maybe.

By the fateful year of 1325, the conflict between the two sides had increased and border skirmishes were quite common. In July of 1325, the Bolognese forces attacked Modenese farms, burned several fields and even killed people before retreating back into their lands. This was again repeated the following month ensuring that severe losses were inflicted on the Modenese.

Passerino Bonacolsi was furious and planned his revenge. In September of 1325, he took an army and laid siege to the fort of Monteveglio, which was an important protective fort for the Bolognese (along with the fort of Zappolino). Monteveglio was of great strategic importance and was quite well protected. However, the fort authorities who were secretly imperial supporters surrendered the fort without putting up a fight. This was a big victory for Passerino Bonacolsi and Modena.

Now the history (or the story) takes a rather weird turn, as it is alleged that amid all this confusion and chaos some Modenese soldiers entered Bologna and somehow reached the town’s center undetected. Here in the main well of the town, rested a wooden bucket that was filled with Modenese loot. The Modenese soldiers stole this bucket, to humiliate the Bolognese and brought it back to Modena.

Somehow the Bolognese were very furious with this incidence of their bucket being stolen & asked back for it. When their demand was refused, Bologna declared war on Modena! Although the War of Bucket certainly did occur but was this caused because the Bolognese wanted their wooden bucket back, as many sources mention? To understand the real situation, we have to take a closer look at the events that followed afterward.

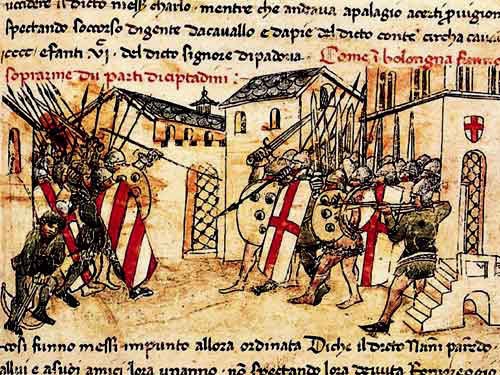

The loss of Monteveglio was a great loss for Bologna and war would be soon declared in Bologna, to avenge their loss. It was on 15 November in 1325 that the War of the Oaken Bucket took place. Bologna managed to muster up 20,000 to 30,000 infantry soldiers and 2000 to 2500 cavalry knights. In response, the Modenese army managed to gather only about 5000 to 8000 infantry soldiers and about 2000 to 2500 cavalry knights.

Clearly, the Bolognese army was much larger than what Modena had but was it really better than their rivals? The answer to that would be an emphatic no. The Bolognese infantry apparently superior numerically consisted of forcefully conscripted ill-equipped & inexperienced people. In contrast, the Modenese infantry consisted of well equipped & well-trained and experienced professional soldiers.

The war of the Bucket, which is also known as the Battle of Zappolino, which took place in Zappolino in the Bolognese territory had a dramatic beginning. The initial attack was initiated by the Bolognese who divided their army into 2 parts. One-part laid siege to the fort of Monteveglio, which initially had belonged to Bologna but now was under the control of Modena. The second half of the army was designed to prevent the advance of Modenese towards Monteveglio.

The Modenese after much difficulty were successful in bypassing the Bolognese army and moved towards the important Bolognese fortress of Zappolino. Bolognese had already lost their fort in Monteveglio to the Modenese and were in no position to lose the fort of Zappolino too to the Modenese. So, the Bolognese army which had laid siege to the fort of Monteveglio were forced to lift their siege on the castle and march out and join the other half of their army, to regroup together and march to Zappolino, to try to stop the Modenese.

The actual fighting of the Battle of Zappolino, took place a couple of hours before sunset on 15 November 1325, with both armies facing each other. However, as has been previously mentioned the Bolognese infantry was superior in number but lacked the fighting skills that the Modenese had. The battle was over by nightfall with a decisive victory for Modena. The Bolognese lost 2500 men whereas the Modena lost just 500 men. The remaining Bolognese soldiers escaped from the battlefield trying to save their lives. The War of the Bucket had ended.

The following day the victorious Modenese army destroyed many fortifications of the Bolognese and finally reached the walls of Bologna itself. The Modenese army did not attempt to lay siege to the city but just put their camps outside the walls. They held a 3-day long celebration party mocking the Bolognese, who did not have any other option but to watch. After 3 days the victorious Modenese army withdrew and went back to their own city. However, on their way out some soldiers of the Modenese army stole a wooden bucket from one of the wells present outside the city walls as a prank.

In contrary to the popular misconception, the war of the bucket was not a war for bucket. The stealing of bucket by the Modenese occurred after they had won the war and it was not the cause which initiated the war of a bucket, as mistakenly presumed by many. The reason for this is obvious – Placing a wooden bucket filled with Modenese loot in the center of the city in Bologna, near a well is a ridiculous proposition. Besides a Modenese soldier could never reach the city center of Bologna undetected.

The real reason why Bologna declared war on Modena was for many understandable practical reasons. Bologna was at odds with Modena for a long time and the fall of the fort of Monteveglio to Modena added fuel to the fire. Besides as staunch followers of the Papacy, they were very hostile to Passerino Bonalcosi. Further, the fact that the Bolognese army was much bigger than the Modenese army also made them believe that they could win any war.

Now comes the most important question – why did the Modenese soldiers steal a wooden bucket from Bologna? Besides the fact that they did it as a prank, there was another logic too. The Modenese were experts in making Artesian Wells, where there was no need for a bucket to take out the water. However, the Bolognese did not know how to make Artesian Wells and hence they used traditional wells, which needed a bucket. So, by stealing the wooden bucket, the Modenese soldiers were ridiculing the Bolognese, implying that they were so inferior that they could not even take out water from a well, without a bucket.

The Bolognese wooden bucket was kept as a trophy in the Modenese cathedral. Later this was replaced by a replica and the original one was transferred to the city hall of Modena, where it remains to this day. However, some people have claimed that this bucket may be also a very old replica and not the real bucket stolen by the Modenese in 1325. Though a concrete proof for this is lacking.

After the war ended nothing more happened for some time. In January 1326 a peace treaty was signed between the two sides. According to the terms of treaty Modena returned Monteveglio and other castles & lands of Bologna, occupied during the Battle of Zappolino back to the Bolognese. Bologna for its part paid heavy war reparations to Modena, in lieu of the castles and lands returned back to the Bolognese. So, in practical terms, the War for the Bucket had no useful outcome and practically ended in a status quo that was present before the war.